Elizabeth Mullineaux BVM&S, DVM&S, CertSHP, MRCVS, RCVS Recognised Specialist in Wildlife Medicine (Mammalian), Secret World Wildlife Rescue

Introduction

Wildlife groups and Defra have worked together to update the Badger Rehabilitation Protocol (‘The Protocol’) first published in 2003. The Protocol provides guidelines about all aspects of how badgers should be rehabilitated and released. This article details the components of the Protocol in relation to reducing the risk of bovine TB transmission to cattle. Defra has been involved in updating this Protocol to promote best practice for the rehabilitation of badgers, but not to encourage the practice of badger rehabilitation.

Badger Rehabilitation Protocol

In 2000 the then Ministry for Agriculture Fisheries and Food (MAFF) questioned the responsibility of wildlife groups in their release of badgers back to the wild, with respect to the possible transmission of TB to cattle. Wildlife groups, farmers and scientists were brought together to discuss this subject. As a consequence, wildlife organisations produced a Protocol for best practice, with the purpose of returning healthy badgers back to the wild, with high regard for animal welfare and for the control of disease. The Protocol was published in 2003.

In March 2017, Defra again asked for wildlife groups to meet for a workshop on badger rehabilitation and bovine TB. All attendees agreed that the Protocol would be updated so that it remains relevant to the current TB situation and policy. The new Protocol is the result of that work.

The Protocol has a strong emphasis on testing for and preventing any possible transmission of TB to badgers, cattle and other animals during the rehabilitation process. The relatively small numbers of badgers involved and the low incidence of disease recorded in these animals [1] mean that the real risk is low.

Background

An estimated 400 badgers are rehabilitated and released in England each year. Most of these badgers are rehabilitated by wildlife groups on the grounds of animal welfare. The process of rehabilitation provides an opportunity for healthy badgers to be released back into the wild. Many badgers that come in to captivity are too injured, unwell, or old, for release back to the wild to be in their best interest – these animals are euthanised at the first possible opportunity. Adult badgers are usually released where found, whilst cubs are grouped together and released at a different release site.

Bovine TB is a disease in cattle caused by Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis) infection. M. bovis is able to affect a wide range of species including humans, cattle and badgers. There is no doubt that both cattle and badgers (in common with other wild mammalian species [2]) suffer from the disease and infected badgers are able to maintain and spread infection [3].

Those dealing with badgers in a rehabilitation situation must be aware of the possible risk of M. bovis infection and take suitable precautions. Excretion of bacteria in infected badgers may occur in saliva, urine, faeces and pus from wounds and lymph node abscesses. Badgers may also transmit infection via contaminated saliva during social disputes that result in wounding (‘territorial’ wounds). Clinical signs of TB in badgers, as in other species, are typically weight loss leading to emaciation.

The Protocol details testing regimes for rehabilitated badgers to reduce zoonotic risks (risk of transmitting the disease from badgers to people) in those handling badgers, and to reduce the risk of disease transmission to other animals, including livestock. Maintaining the confidence of landowners providing release sites for badger cubs is key to the rehabilitation of these animals.

Where are badgers released?

Wildlife species should not be released unless they are able to both survive and not pose a disease risk. Adult badgers should always be released as close as possible to the location in which they were found. Ideally, cubs should be released back to their natal sett in a process of Monitored Natal Return (MNR). Professional help should be sought by contacting a specialist centre such as Secret World Wildlife Rescue (SWWR) or Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA).

If a cub cannot be released using MNR, the suitability of the release site needs to be considered in regards to bovine TB. Since 2014, England has been split into three risk areas reflecting regional variations in the incidence (levels) of bovine TB: High Risk Area, Edge Area and Low Risk Area. Once cubs have successfully passed through the triple testing regime (see below), they should be released in groups at sites as close as possible to where they were found, ideally in an area of equal or higher risk (e.g. Edge Area cubs should be released in Edge Area or High Risk Area). Cubs should be mixed where possible with other cubs from the same risk area.

Testing for TB prior to release

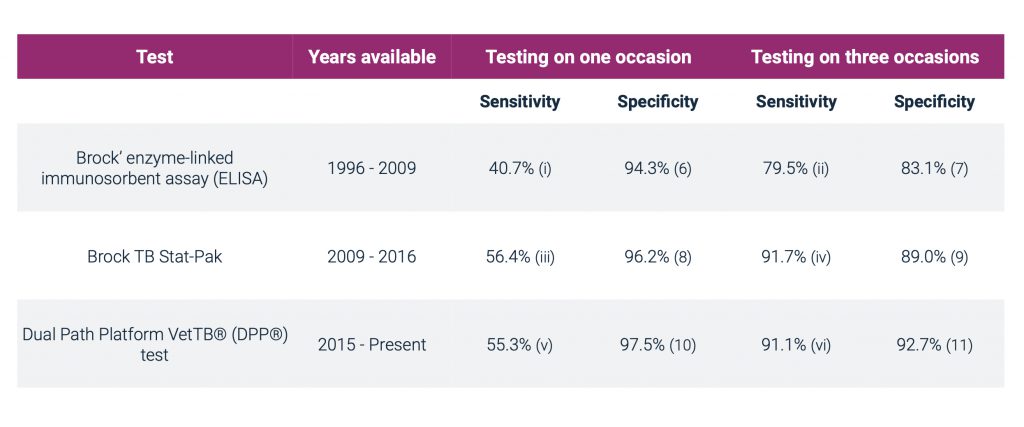

Serological (blood) tests are the most appropriate tests for M. bovis in live badgers. Blood tests typically have low sensitivity but high specificity [4]:

- Sensitivity – the probability that a test will correctly identify an infected animal as positive, i.e. the higher the sensitivity of the test, the lower the probability of incorrectly classifying an infected animal as uninfected.

- Specificity – the probability that a test will correctly identify an animal that is free from infection as negative, i.e. the higher the specificity, the lower the probability of incorrectly classifying an uninfected animal as infected.

Testing an individual animal with a blood test on more than one occasion increases the sensitivity of the test but reduces test specificity.

Blood tests for TB in badgers

Point estimates have been used to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of triple testing. The uncertainty associated with each estimate is not captured here. The Stat-Pak estimate is cub specific. Sensitivity will be greater in animals with more severe pathology and this variation is not captured by our estimates.

(i) Clifton-Hadley, R.S.A. Sayers, and M.P. Stock (1995). Evaluation of an ELISA for Mycobacterium bovis infection in badgers (Meles meles). Veterinary Record 137.22: 555-558

(ii) Forrester, G.J., Delahay, R.J., Clifton-Hadley, R.S. (2001). Screening badgers (Meles meles) for Mycobacterium bovis infection by using multiple applications of an ELISA. Veterinary Record, 149, 169-172

(iii) Chambers, M.A., Waterhouse, S., Lyashchenko, K., Delahay, R., Sayers, R., & Hewinson, R.G. (2009). Performance of TB immunodiagnostic tests in Eurasion badgers (Meles meles) of different ages and the influence of duration of infection on serological sensitivity. BMC Veterinary research, 5 (1), 42.

(iv) Tomlinson and Wilson (2009). Badger Rehabilitation Protocol Review Final Report to RSPCA. RSPCA, Horsham.

(v) Animal and Plant Health Agency. (2017). Validation of Diagnostic Assays at APHA: DPP Vet TB lateral flow test for detection of TB in badgers. Report form for the submission of APHA Diagnostic Test Validation Data (TV290).

Point estimates have been used to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of triple testing. The uncertainty associated with each estimate is not captured here. The Stat-Pak estimate is cub specific. Sensitivity will be greater in animals with more severe pathology and this variation is not captured by our estimates.

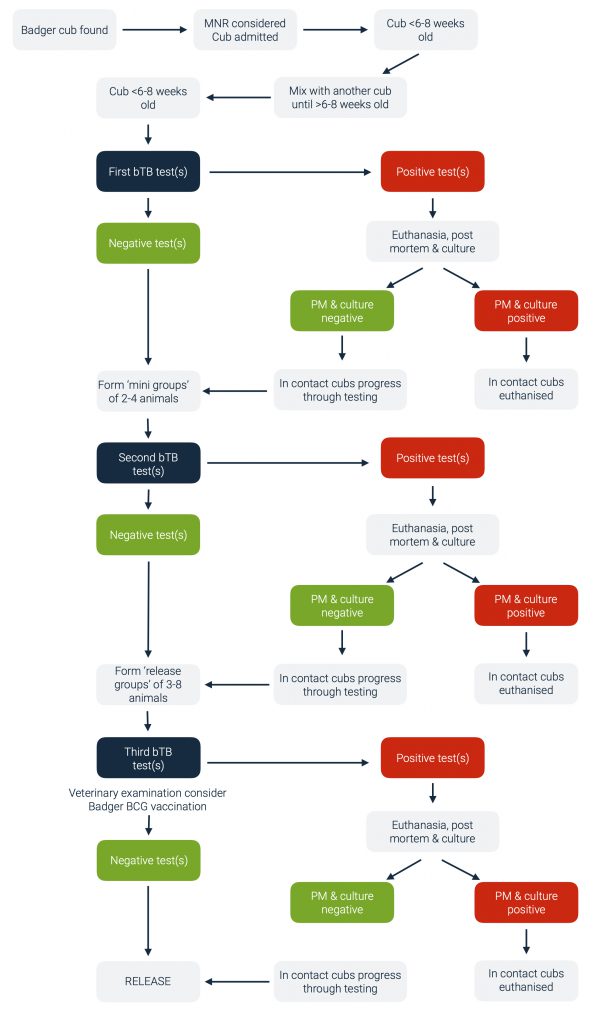

Protocol for testing badger cubs

If a badger cub cannot be returned to its natal sett using Monitored Natal Return [12], it needs to be tested for TB. Cubs need to be mixed with other badgers because they are social animals and need to be held in captivity for some months before being old enough to survive in the wild. The construction of such ‘release groups’ means that individual cubs cannot be released back to the location where they were found and instead the group is released at a new site.

Badger cubs being reared and rehabilitated for release have been ‘triple tested’ by the RSPCA and SWWR since 1996. The three tests are performed at approximately equal intervals during the 4-6 months of the badger rearing process in an attempt to ensure that badger cubs are free of M. bovis infection prior to release.

The flow chart below summarises the protocol for testing badger cubs. Cubs under 8 weeks old need to be mixed with another young cub (or cubs) prior to testing. The minimal number of young badger cubs may mean that they have to be moved some distance to a suitable rehabilitation centre. However, the aim should always be to keep cubs in an area of similar TB status in cattle to where they were found. Cubs under 8 weeks old should ideally only be mixed into ‘mini groups’, pairs or groups of three. Mixing of untested cubs must be kept to a minimum.

The first blood test for TB should be carried out from 6-8 weeks old when maternal antibodies have waned. On receiving the first negative TB test results (see below regarding test positive cubs), all cubs should be mixed to form ‘mini groups’ and allowed time for social interaction to take place. Each ‘mini group’ of cubs should then be blood tested for a second time, at least four weeks after the last cub in the group was first tested. On receiving the second negative TB test results, two or more ‘mini groups’ may be mixed together to form a suitable ‘release group’. All cubs in a release group should be tested for a third time as near as possible to the time of release and at least 4 weeks after the second test. Anaesthesia for the third blood test allows full health inspection of the animal prior to release.

Badger cubs can only be released following three consecutive negative blood test results. Cubs testing positive to ANY of the three TB blood tests must be immediately euthanased. A licence is required for euthanasia of badger cubs in these circumstances. The test positive cub is examined post-mortem and culture of tissue samples is carried out for M. bovis. This process remains the gold standard for TB diagnosis [13]. Culture of M. bovis takes around twelve weeks. There are two possible outcomes of the post mortem and culture result:

- If the euthanased animal is post mortem and culture negative, the remaining group can continue the release protocol.

- If the euthanased badger is positive on post mortem and/or culture examination, the remaining animals in the group must be euthanased.

Rehabilitated badger cubs should be tested for TB to help prevent zoonotic risks in those handling these animals, which often require close contact and bottle feeding, and reduce the risk of disease transmission to other animals, including livestock. Maintaining the confidence of landowners providing release sites for badger cubs is key to the rehabilitation of these animals.

Badger vaccination

Since 2010, a BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guérin) vaccine for badgers has been licenced and available to wildlife groups for vaccination of badgers against TB. In badger cub groups there is a clear argument for vaccination, both to protect the group and to enhance landowner confidence in the release process. BadgerBCG is licenced for use in cubs from 12 weeks old. Badger cubs are usually BCG vaccinated prior to release, usually at the time of the third TB blood test.

The vaccine has been shown to reduce the severity and progression of TB in badgers [14] and is therefore some potential benefit to individual animals. The benefits of BCG are however best seen on a population basis when large groups of badgers are vaccinated [15]. In badger adults, there is therefore an argument that vaccination of an individual is of limited benefit, unless the other badgers in the area or group are also vaccinated. Where vaccination of adults prior to release is possible, no disadvantages are evident.

Summary

The revised Badger Rehabilitation Protocol aims to describe best practice for badger care, rehabilitation and release. As a result of the importance attached to the issue of eradicating bovine tuberculosis in England, the Protocol has a strong emphasis on testing for and preventing any possible transmission of this disease to badgers, cattle and other animals during the rehabilitation process.

In reality, the small numbers of badgers involved and the low incidence of disease recorded in these animals, mean that the real risk is low. Since our wish however is that all interested parties have confidence in the process we will continue to review and update the policy as new scientific information and new diagnostic tests become available.

References

1. Mullineaux, E., Kidner, P. (2011). Managing Public Demand For Badger Rehabilitation In An Area Of England With Endemic Tuberculosis. Veterinary Microbiology, 151, 205-208.

2. Delahay, R.J., Smith, G.C., Barlow, A.M., Walker, N., Harris, A., et al. (2007). Bovine tuberculosis infection in wild mammals in the South-West region of England: A survey of prevalence and a semi-quantitative assessment of the relative risks to cattle. Veterinary Journal, 173, 287-301.

3. Corner, L.A.L. (2006). The role of wild animal populations in the epidemiology of tuberculosis in domestic animals: How to assess the risk. Veterinary Microbiology, 112, 303-312.

4. Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board. (2015). TB hub. Tuberculin skin testing.

5. Point estimates have been used to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of triple testing. The uncertainty associated with each estimate is not captured here. The Stat-Pak estimate is cub specific. Sensitivity will be greater in animals with more severe pathology and this variation is not captured by our estimates. Thanks to F. Smith for calculating the triple test specificity and sensitivity of the DPP test.

6. Clifton-Hadley, R. S., A. R. Sayers, and M. P. Stock. (1995). Evaluation of an ELISA for Mycobacterium bovis infection in badgers (Meles meles). Veterinary Record 137.22: 555-558.

7. Forrester, G.J., Delahay, R.J., Clifton-Hadley, R.S. (2001). Screening badgers (Meles meles) for Mycobacterium bovis infection by using multiple applications of an ELISA. Veterinary Record, 149, 169-172.

8. Chambers, M. A., Waterhouse, S., Lyashchenko, K., Delahay, R., Sayers, R., & Hewinson, R. G. (2009). Performance of TB immunodiagnostic tests in Eurasian badgers (Meles meles) of different ages and the influence of duration of infection on serological sensitivity. BMC veterinary research, 5(1), 42.

9. Tomlinson and Wilson (2009). Badger Rehabilitation Protocol Review Final Report to RSPCA. RCPCA, Horsham.

10. Animal Plant Health Agency. (2017). Validation of Diagnostic Assays at APHA: DPP Vet TB lateral flow test for detection of TB in badgers. Report form for the submission of APHA Diagnostic Test Validation Data (TV290).

11. Smith, F. (2018). Reference for the specificity and sensitivity of the DPP test. Calculated from Animal Plant Health Agency. (2017). Validation of Diagnostic Assays at APHA: DPP Vet TB lateral flow test for detection of TB in badgers. Report form for the submission of APHA Diagnostic Test Validation Data (TV290).

12. Parr, A. (2016). The Rehabilitator’s & Badger Enthusiast’s Handbook: Returning Badger Cubs (Meles Meles) to the Natal Sett Following Short Term Rehabilitation. Lancashire Badger Group, Lancaster.

13. Gallagher, J., Horwill, D.M. (1977). A selective oleic acid albumin agar medium for the cultivation of Mycobacterium bovis. Journal of Hygiene, 79, 155-160.

14. Chambers, M.A., Rogers, F., Delahay, R.J., Lesellier, S., et al. (2011). Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination reduces the severity and progression of tuberculosis in badgers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 278 (1713), 1913–1920.

15. Carter, S.P., Chambers, M.A., Rushton, S.P., Shirley, M.D.F., Schuchert, P., et al. (2012). BCG Vaccination Reduces Risk of Tuberculosis Infection in Vaccinated Badgers and Unvaccinated Badger Cubs. PLoS ONE 7 (12), e49833. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049833