The Animal & Plant Health Agency (APHA) is responsible for delivering the bovine tuberculosis (bTB) eradication programmes in England, Scotland and Wales. Good diagnostics are central to any disease eradication programme and APHA carries out a large amount of bTB testing to support this effort.

When a TB incident occurs, APHA field vets carry out a disease investigation to gather information about how TB infection could have entered the herd and whether it could have spread. To support this investigation, microbiological culture of the TB bacterium, Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis) is attempted from tissue samples taken from the carcases of slaughtered animals at post-mortem inspection.

If M. bovis is cultured in the laboratory, genetic analysis is carried out to determine the particular strain of the bacterium. With this information APHA can establish the degree of genetic relatedness of the M. bovis strain to strains from other TB breakdown herds, which in turn helps identify the most likely origin of TB infection for the affected herd.

Previously, a combination of two molecular techniques known as genotyping was used at APHA to characterise the M. bovis isolates into different strains (genotypes), which tend to be geographically localised. The technique of whole genome sequencing (WGS) replaced genotyping on 19 April 2021. As the name suggests, instead of targeting specific regions of the bacterium’s genetic material, it determines its entire DNA sequence. WGS allows characterisation of different strains of the M. bovis bacterium at greater resolution than genotyping. This ultimately allows a greater degree of certainty about the origin of TB infection for a herd and increases our understanding of how TB spreads both locally and nationally.

Glossary

DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid): the main genetic material of animals, plants, fungi, bacteria and many viruses. It carries the genetic instructions for the organism’s development, function, growth and reproduction.

Epidemiology: the study of disease in a population and the factors that determine its occurrence over time. It examines the distribution of disease and risk factors for infection, in order to identify opportunities for intervention to control the disease.

Genome: an organism’s complete set of DNA.

Genotype of M. bovis: the strain of M. bovis, denoted by a number and letter e.g. 17:a.

Microbiological culture: a method of growing organisms (e.g. bacteria) by letting them reproduce in predetermined culture medium under controlled laboratory conditions.

Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis): the bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB) in cattle.

M. bovis isolate: a microbiological culture of M. bovis bacteria.

Phylogenetic analysis: the study of evolutionary development of a species, a group of organisms, or a particular characteristic of an organism.

Phylogenetic tree: a branching diagram or “tree” showing the evolutionary relationships among various organisms (their phylogeny), based on similarities and differences in their physical or genetic characteristics.

Hotspot area: A hotspot is an area of enhanced bovine TB surveillance set up in the Low Risk Area (LRA) of England around a herd (more usually a cluster of herds) of Officially Tuberculosis Free Withdrawn (OTF-W) status, where the breakdowns are of an uncertain origin, i.e. there is no clear explanation or route of infection.

WGS clade: a group of phylogenetically related isolates based on similarities across their whole genome sequences.

Whole genome sequencing (WGS)

Genetic material (DNA) is found in all living organisms, including bacteria. Each M. bovis bacterium contains unique DNA which carries the genetic instructions for its development, function, growth and reproduction. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is a molecular technique used to characterise the entire DNA content of an organism.

How is WGS different to genotyping?

Genotyping was the method of genetic typing previously used by APHA to characterise M. bovis isolates. It involved a combination of two techniques; spoligotyping and variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) typing. The techniques targeted specific regions of the bacterium’s DNA sequence in order to characterise it and assign a genotype.

Spoligotyping is a rapid, PCR-based method that checks for the presence or absence of 43 unique short DNA sequences (or spacers) in a particular region of the genome of M. bovis (and related bacteria) containing repetitive sequences. Each pattern found has a spoligotype number associated to it such as 9, 17, 35, etc. VNTR typing is based on the number of repetitions of short DNA sequences found in six specific regions of the bacterial genome. Each unique spoligotype and VNTR pattern combination is defined by a number followed by a letter, such as 9:a, 9:b,17:b, 25:a, 25:b, 35:a, 10:u etc., where the letter denotes the frequency in decreasing order of that particular VNTR pattern within a spoligotype in GB (9:a being more common than 9:b, etc.).

WGS is a relatively new technique used by APHA which has now replaced genotyping of M. bovis isolates. Instead of targeting specific regions of the bacterium’s genome, WGS involves the analysis of its entire DNA sequence. This allows a greater degree of differentiation (‘granularity’) between M. bovis isolates. The technique involves breaking the bacterial genome into smaller fragments which are sequenced individually and then put back together in the correct order.

What are the limitations of genotyping, and how is WGS an improvement?

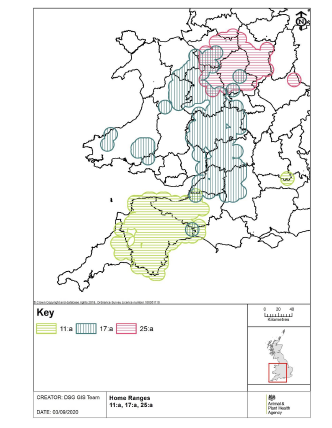

Genotyping targeted specific regions of the bacterium’s DNA sequence, and looked for differences in the repeat patterns of these regions between isolates. This meant that genotyping allowed limited differentiation between M. bovis strains. The M. bovis bacterium has limited genetic diversity. There were only 22 major genotypes which accounted for 96% of all isolates. Each M. bovis genotype was associated to a particular geographical area (home-range) where it was commonly found. APHA used to generate “home-range” maps of the major M. bovis genotypes in GB. The most frequent genotype found in England in 2019 was 17:a, followed by 25:a and 11:a. These three genotypes accounted for 49% of all M. bovis isolates identified in 2019 and cover extensive areas in the south west and west of England, and Wales (see map to the left from the 2019 England bTB epidemiology report).

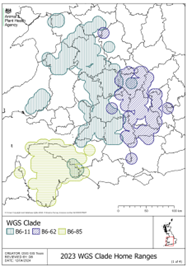

The three WGS clades of M. bovis of most commonly isolated in England, based on data from 2023, were B6-11, B6-62 and B6-85 (see map to the right from the 2023 England bTB epidemiology report).

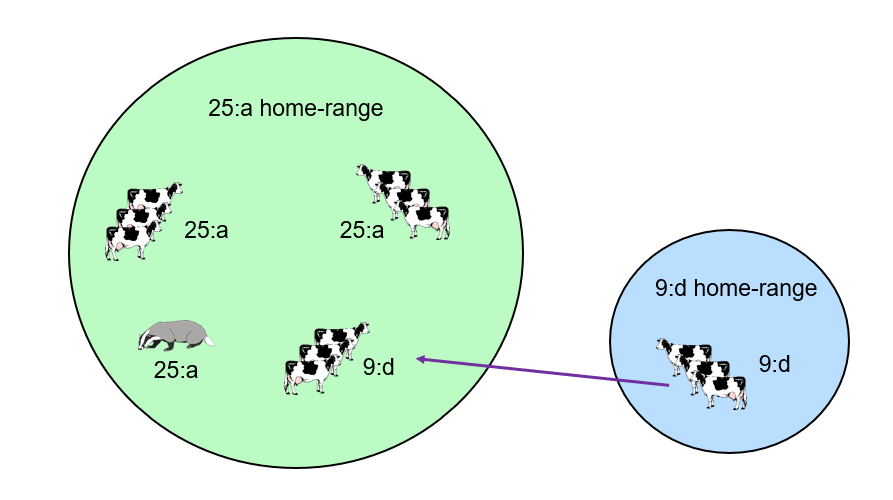

Genotypes were helpful to distinguish local sources of TB infection from breakdowns caused by introductions of infected cattle moved over long ranges (‘purchased’ infection). If the M. bovis genotype isolated from a TB breakdown herd was not one found locally (i.e. it is out of home-range), then this indicated that TB infection was most likely introduced into the herd by cattle movements from outside of the home-range area. However it was more difficult to distinguish transmission routes between cattle herds that are infected with the same genotype of M. bovis and were located within the home range of that genotype.

The schematic diagram to the right illustrates this. A cluster of three TB breakdowns had occurred in a parish in the same year. Two breakdowns have M. bovis genotype 25:a (the local genotype), whereas one breakdown has genotype 9:d which was out of home-range. This meant that the 9:d breakdown was most likely caused by long range movements of cattle into the herd from an area where 9:d genotype was commonly found. Due to the limited resolution of genotyping, it was more difficult to be confident about the most likely source of infection for the two breakdowns with genotype 25:a. TB could had entered the herd via local cattle movements, contact with infected neighbouring cattle, or indirect/direct contact with infected badgers.

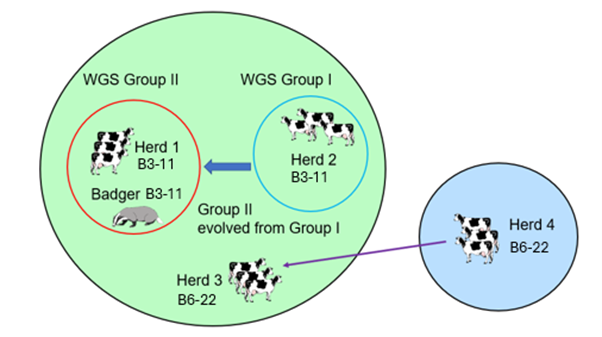

WGS can provide greater and more accurate discrimination between strains of M. bovis than genotyping. This potentially allows APHA to distinguish local sources of infection and identify transmission pathways between cattle herds, even within a home-range. It can also identify whether recurrent TB breakdowns have been caused by residual infection in the herd from a previous breakdown, or from a new introduction.

In the above scenario, WGS could be used to assess the genetic relatedness of M. bovis isolates from the cluster of TB breakdowns and provide more information about origin and transmission routes of infection between cattle herds. The schematic diagram to the left shows the benefits of WGS in this example. By applying WGS, the two 25:a breakdown herds and the 25:a badger can be subdivided into two different genetic sub-groups (all the isolates with a 25:a genotype were clade B3-11), Group I and Group II. In this case, WGS can also determine the direction of transmission of TB infection. If Group II is descended genetically from Group I, this suggests that herd 2 became infected first and then infection spread to herd 1 and the badger. Genotyping would not have been able to differentiate between Group I and II.

Q&A

Yes. APHA implemented routine use of WGS for typing of M. bovis isolates in April 2021. WGS replaced genotyping which was the previous technique used.

The main benefit of WGS is that it provides greater and more accurate differentiation between M. bovis isolates when compared to genotyping. This allows assessment of genetic relatedness between isolates and provides additional information on evolutionary relationships. In practice, APHA can use this information to better assess transmission pathways of M. bovis to understand how and where it has spread.

APHA uses WGS to characterise isolates of M. bovis cultured from cattle slaughtered for TB control. This provides information about the genetic relatedness of M. bovis strains, where they have come from and how they have evolved. WGS is an important tool used by APHA for investigating TB breakdowns and possible transmission pathways between cattle herds. WGS supports study of the spread of TB in the local and national cattle population and the factors that affect it over time. At farm level, WGS helps APHA field vets to identify the most likely source of TB infection for a breakdown herd, and also whether it has spread to other cattle herds. Once APHA is aware of the likely origin of a breakdown, they can advise farmers on measures they could take to reduce the risk of further infection entering the herd.

The M. bovis bacterium exhibits limited genetic diversity with over 99% of the genome being identical among isolates. Differences in the DNA sequences are used to discriminate between M. bovis isolates. These differences are called single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or “snips”. The fewer differences (SNPs) between two isolates of M. bovis, the closer their genetic relatedness.

APHA uses phylogenetic analysis to visualise the relatedness of M. bovis isolates. This involves arranging the different isolates on a phylogenetic diagram or “tree” – a family tree of M. bovis. The population of M. bovis isolates in GB can be divided into around 30 distinct WGS clades which are geographically isolated. When placed on a map, these WGS clades correspond to dispersed genotype home-ranges.

Please see this as an example of a phylogenetic tree showing a small number of samples indicated by blue dots. Samples sitting in the same vertical line are identical, and numbers along the horizonal lines indicate the number of SNPs different from the ancestor (towards the left of the tree).

Phylogenetic trees are a way of visualising the genetic relatedness of M. bovis isolates. This helps to assess the evolutionary relationships between isolates in space and time, and provide information about how and where TB has spread between cattle herds, and between cattle and wildlife.

Instead of genotypes, WGS clade labels are used to denote related strains of M. bovis, for example “B6-11”. As WGS provides greater differentiation between strains of M. bovis, some genotypes can be split further into multiple WGS clades e.g. genotype 9:d is split into eight distinct WGS clades. This means that 9:d isolates can be quite different across their genomes. Conversely, a few genotypes are assigned to the same WGS clade. This means that isolates with these genotypes are quite similar across their genomes and therefore more closely related than suggested by their genotype.

The majority of genotypes are assigned to a single WGS clade however 1:1 correlation between the two schemes is not possible.

Yes. Records of historical genotypes of M. bovis isolates are still available to APHA staff involved in the control of bTB and its epidemiology.

Like all genetic typing methods, you need to isolate the bacterium in the first place to be able to carry out WGS. So, like genotyping, WGS can only be carried out once the TB bacterium has been isolated by microbiological culture. It takes a minimum of six weeks to culture M. bovis, and then WGS is carried out on the isolate. For a small proportion of isolates, the quality of the sample does not allow WGS to be carried out.

WGS has only used by APHA since June 2017, and not many M. bovis isolates prior to that date have been sequenced. This means that the current WGS database which new isolates are compared against is limited, but is continually improving as more data is added over time.

Although WGS can provide more information about genetic relatedness of isolates than genotyping, there are limits to the inferences that can be made when interpreting WGS data. For example, it’s often not possible to determine the direction of transmission of M. bovis between different species.

The number of reactor animals sampled for culture and WGS depends on the status of the breakdown (whether the herd’s officially TB free status is suspended or withdrawn), the number of reactors, and previous post-mortem examination and culture results if applicable.

Yes. APHA routinely uses WGS on M. bovis isolates from non-bovine animals such as South American camelids (alpacas, llamas), goats, pigs, and captive deer when investigating TB incidents affecting these species.

Yes. WGS is also used to analyse M. bovis isolates from wildlife species (e.g. road killed badgers) and compare them with isolates from local TB breakdowns in cattle herds and other farmed animals. This allows APHA to assess whether cattle and badgers from the same geographical area are affected by the same strain of the TB bacterium, and to assess the spread of TB strains between geographical areas and across time. For instance, WGS was being used to support TB surveillance in cattle and badgers and understand the epidemiology of bTB in the hotspot area in east Cumbria (HS21), where a link between cattle and badger TB infection was first identified in 2017. Visit GOV.UK to find out more about TB surveillance in wildlife.