Microbiology is the scientific study of microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses and fungi. Bovine TB is caused by infection with the bacterium Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis). Knowledge of the microbiology of M. bovis is useful to provide context for understanding how bovine TB affects a population (epidemiology), and how it is controlled.

History

The organisms causing TB and leprosy in man were first recognised by the famous German physician and microbiologist Robert Koch in 1882. Although not named by him, others proposed the name Mycobacterium for the genus in 1886. Whilst the organism causing TB in cattle was recognised by Koch as being different to that causing TB in man, surprisingly it was not formally named Mycobacterium bovis until 1970.

Genus

The genus Mycobacterium is very large, containing nearly 200 species, most of which do not cause disease or only do so in people with weakened immunity. A group of genetically related species causing TB in humans and other animals is known as the M. tuberculosis complex (MTC). It is thought that they evolved from soil-living organisms, then spreading and diverging with human migrations and with the domestication of cattle [1] [2]. This group contains both M. tuberculosis and M. bovis. Another group, the M. avium complex (MAC), contains M. avium subsp. avium primarily found in birds, and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, the cause of Johne’s disease in cattle, sheep and goats. Rarely, other species of mycobacteria may be involved in cases of TB in animals and humans.

Relationships

The close microbiological relationship between these organisms has important implications for public and animal health. TB in humans is primarily caused by M. tuberculosis, but M. bovis can also be involved in a minority of cases. So it is important that the infecting species is identified in order to determine the source of TB in humans.

The immune response arising from infection with mycobacteria can cross react with similar species and strains of the genus. Crucially, cattle can be infected by M. avium subsp. avium or M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (and more rarely, other mycobacteria) which can cause a cross-reacting immune response. This can compromise the effectiveness of the diagnostic tests for M. bovis, leading to both false positives and false negatives in different circumstances [3]. In practice, cattle infected with M. bovis and also affected by or vaccinated against Johne’s disease are less likely to be detected by the tuberculin skin test.

BCG

Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) is a strain of M. bovis artificially developed at the beginning of the 20th century with reduced virulence. It has been widely used as a vaccine in people globally, as it provides partial protection against TB. A BCG vaccine is currently being developed for use in cattle along with a test to differentiate infected among vaccinated animals [4]. There is a licensed injectable BGC vaccine for use in badgers.

Culture and typing

M. bovis can be grown in vitro in the laboratory from clinical samples such as milk or urine, but more usually from tissue samples collected post mortem in the abattoir. However it is very slow growing and requires special expertise and safety facilities. This means that culture can only be carried out in specialist laboratories and the results of tests necessary to confirm disease may take several weeks to be reported. It is only after growth in the laboratory that the species of Mycobacterium isolated can be identified.

Whole genome sequencing

If M. bovis is isolated and identified in the laboratory, it can be further typed using a genetic typing method called whole genome sequencing (WGS) so that individual strains can be identified. WGS involves analysis of the entire DNA sequence of the bacterium which allows a greater degree of differentiation between M. bovis isolates. The technique involves breaking the bacterial genome into smaller fragments which are sequenced individually and then put back together in the correct order. WGS provides information about the genetic relatedness of M. bovis strains, where they have come from and how they have evolved.

WGS is an important tool for investigating TB breakdowns and possible transmission pathways between cattle herds. It supports study of the spread of TB in the local and national cattle population and the factors that affect it over time. At farm level, WGS helps identify the most likely source of TB infection for a breakdown herd, and also whether it has spread to other cattle herds. Once the likely origin of a breakdown is identified, advice can be given to the herd owner on measures they could take to reduce the risk of further infection entering the herd.

Nature of mycobacteria

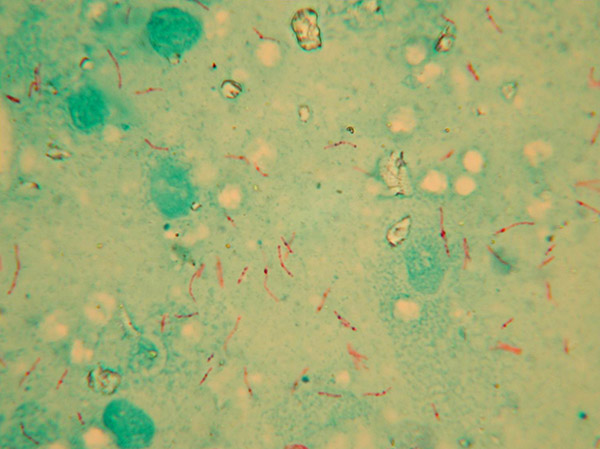

Mycobacteria are unusual amongst bacteria in their robustness, resilience and slow growth characteristics, and the chronic and insidious nature of the diseases that they cause. M. bovis is a facultative intracellular ‘parasite’, meaning that it can survive and thrive inside the host’s macrophages (cells of the immune system that are meant to engulf and destroy the invading bacteria). It has many adaptations to intracellular life and may become quiescent (dormant) or divide very slowly, which enhances its survival. It has a tendency to become walled off in granulomas (small nodules of chronic inflammation) in the tissues.

Mycobacteria have a unique and complex cell wall structure comprising layers of protein, polysaccharide (carbohydrate) and particularly lipid (fat). These components confer structural strength and great resistance, both to attack in the intracellular environment, and enhance survival outside of the host.

Pathogenesis and intracellular life

The pathogenesis of M. bovis is complex and largely attributed to its ability to evade or manipulate the host’s immune response. These strategies facilitate the establishment of the primary infection, its persistence, quiescence and reactivation under favourable conditions. The organism deploys multiple remarkable biochemical, immunological, and genetic strategies to gain access to host macrophages and then resist the usual bacterial killing mechanisms, reprogramming them and thriving in this hostile environment.

Of particular note and importance is the tolerance of mycobacteria to acidic conditions. This is needed because the host acidifies the phagosomes, small envelopes within the macrophages containing the engulfed bacteria intended to kill them. Mycobacteria have evolved to resist this, which has consequences for the ability of M. bovis to survive in other acidic environments, such as silage. The host’s response of granuloma formation (so called ‘walling off of infection’) in its attempt to limit bacterial dissemination, also serves to provide a secure niche protected from the immune response. This reduced exposure to the host’s immune cells also means that a diagnostically detectable antibody response, which is common for other bacterial and in viral diseases, is often delayed for a considerable period. Therefore, tests that measure cell-mediated immune responses, such as the tuberculin skin and interferon-gamma tests are more suitable for the diagnosis of TB in animals and man.

As an obligate aerobe requiring oxygen for survival, M. bovis survives the low-oxygen environment within the granuloma by entering a state of non-replicating quiescence in which it can survive for months or years until conditions become more favourable, perhaps when host immunity wanes through stress or intercurrent disease. The quiescent state is brought about following the increased storage of nutrients, reduction in metabolic pathways and changes in the structure of the cell wall, particularly in its lipid component. These attributes also confer on M. bovis the ability to survive harsh conditions in the environment for considerable periods, maintaining its ability to infect susceptible hosts.

Conclusion

M. bovis is exquisitely adapted for survival in the host for long periods, and establishing chronic infections with a long incubation period that are difficult to detect in the live animal. These same characteristics also allow the organism to survive in the environment for long periods, posing an infection risk to cattle and wildlife from this environmental exposure.

A basic knowledge of the microbiology of mycobacteria is crucial for an understanding of the on-farm risks and the development of disease control strategies.

References

[1] Gutierrez MC, Brisse S, Brosch R, Fabre M, Omaïs B, et al. (2005) Ancient Origin and Gene Mosaicism of the Progenitor of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLOS Pathogens 1(1): e5.

[2] Wirth T, Hildebrand F, Allix-Béguec C, Wölbeling F, Kubica T, et al. (2008) Origin, Spread and Demography of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex. PLOS Pathogens 4(9): e1000160.

[3] Coad, M, Clifford, DJ, Vordermeier, HM, Whelan, AO (2013) The consequences of vaccination with the Johne’s disease vaccine, Gudair, on diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis Veterinary Record 172, 266

[4] Chambers, MA, Carter, SP, Wilson, GJ, Jones, G, Brown, E, Hewinson, RG, Vordermeier, M.(2014) Vaccination against tuberculosis in badgers and cattle: an overview of the challenges, developments and current research priorities in Great Britain Veterinary Record 175, 90-96.